THE PROJECT

THE PROJECT

Researching Dutch and Flemish art at the Picker Art Gallery

Over the course of the 2019–20 academic year, the Picker’s Dutch and Flemish collection has been the focus of an in-depth research project. In order to find out as much as possible about their art historical significance and provenance, this group of almost thirty objects has benefited from up-close study as well as sustained inquiry of archival and secondary sources.

Research on a museum collection typically happens in a very systematic manner. A good starting point for such investigations is a close examination of the objects themselves. In the case of a painting, one may note the materials and techniques used and search for a signature. The back of a painting (typically called the reverse, or verso) can also hold significant clues, such as old inventory numbers, stamps, or inscriptions that say something about where a work has been in the past.

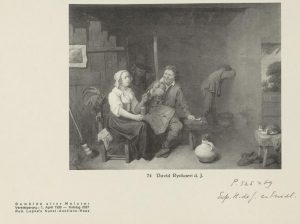

Stamps were found on the reverses of several paintings, including Portrait of a Woman and Men Smoking in an Interior. The first was used by the Austrian Federal Monuments Office (Bundesdenkmalamt) between 1920 and 1934 to approve objects for export. The second appears to contain the Czech words for “Prague” and “Monument.” It could indicate the export of this painting out of Czechoslovakia in the past.

Works on paper, including drawings and prints, could show collector’s marks or contain watermarks. Careful examination of artworks in this manner is usually followed by a trip to the museum’s own internal archive. For every object in the collection a dedicated research file is kept. This contains basic information such as the manner in which the museum acquired the artwork—for instance files that document its donation or purchase on the art market—as well as details about previous loans, and condition and restoration reports. This file also represents the current state of the institution’s knowledge about the work, and includes the documentation of past research efforts.

After this initial inspection of the work and its object file, a logical next step is to survey relevant literature to find out if the artwork in question has been previously published or assessed by other experts. This can yield valuable information, such as earlier interpretations of its subject matter, longstanding attributions (the artist or artist’s workshop that is credited with creating an object), and past owners. Art historical literature such as monographs (a detailed history of an artist and his or her work) can also be helpful to track the movements of artworks through different time periods. A page from Wilhelm Bode’s Adriaen Brouwer: sein Leben und seine Werke (“Adriaen Brouwer: His Life and His Work”; Berlin, 1924), for instance, reproduces the Picker’s painting as its first image. The caption states that it was in the collection of Maximilian Kellner (1869–1940) at that time.

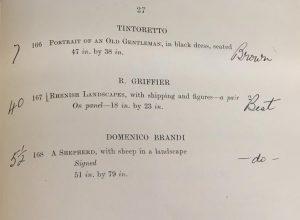

The ownership history of artworks, referred to as their provenance, is of interest to museums for multiple reasons. One is the insight that such information provides into the appreciation, functions, and physical conservation that objects have enjoyed—or endured—during their former lives. Another reason is concern regarding extensive looting of art objects in Europe during the expansion of Nazi-Germany, from 1933–1945. Research efforts therefore center on this period in particular. Databases containing historic auction results often provide further avenues for research. They might lead, for instance, to the archives of collectors or art dealers who were revealed to have previously owned the work. Furthermore, identification of an object in past auctions can lead to annotated auction catalogues that could, in turn, list additional seller and/or buyer names.

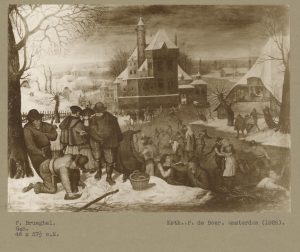

Old photographs kept in specialized photo documentation archives, such as those at the Frick Reference Library in New York City or the Netherlands Institute for Art History (RKD) in The Hague often contain valuable provenance information as well. They can also provide keen insight into a work’s changed physical condition and conservation history. For example, photographs of paintings now in the collection of the Picker were found in the photo documentation archive of the RKD. Such records often contain important information in their captions and inscriptions, for instance the names of previous owners.

Update 06/13/2020: A recent trip to the RKD in The Hague, which opened up to visitors again on June 2, allowed follow-up research on information previously discovered in the photo documentation archive. The image of the Picker’s painting by Pieter Brueghel II, seen to the right, lists the name of art dealer P. de Boer. Another image revealed that the work was previously owned by Baron Léon Janssen (1849-1923), in Brussels. Auction catalogues from the sale of his collection in 1927, and an illustrated collection catalogue kept at the RKD, showed that the painting came to Janssen from the collection of “the painter Den Duyts,” likely Gustave den Duyts (1850-1897), and was sold to the Amsterdam dealer De Boer for 1,800 guilders at the 1927 sale.

Sometimes physical inspection of the artwork and archival research go hand in hand: an old auction number “167” recorded on the reverse of the panel by Robert Griffier, for instance, makes it likely that this painting was one of a pair sold with the same lot number in London in 1939.

Despite extensive efforts, researchers and curators are often left with many open-ended questions regarding the works in their collections. Due to the closure of museums, archives, and libraries around the world as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, some of the research that was planned for this year has been halted. Take a look here at some of the mysteries that remain—for now!