While we often think of an artwork as the result of an individual creative process, sixteenth and seventeenth-century paintings were usually produced in workshops where many hands were at work. In addition to a master painter, assistants in various stages of their training helped to prepare paints, execute works based on the master’s designs, and make precise copies of completed works. Styles and compositions that were particularly popular could also be copied by other artists. Sometimes these copies were done in a much later period, and after prints rather than the original painting.

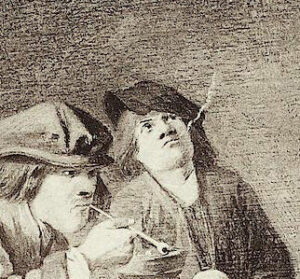

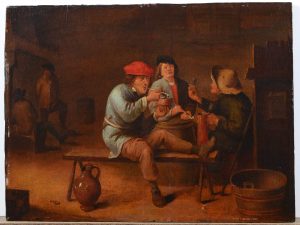

Multiple versions of Men Smoking in an Interior are known today, but this tavern scene probably did originate in the workshop of Adriaen Brouwer. Evidently done by different hands, most versions likely follow a lost original by Brouwer. Experts think that our painting was created by a relatively skilled artist, and at one point could have included final touch ups by Brouwer himself.

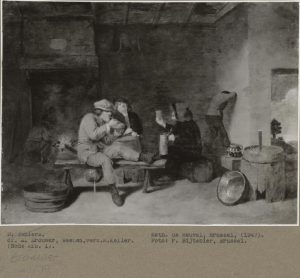

An examination of the painting under ultraviolet (UV) light has revealed significant repairs to the abraded background done during at least two restoration campaigns. Materials that appear to have the same color in regular light, can fluoresce very differently under UV light. As such, this process can reveal the extent of previous restorations or traces of composition elements that are no longer detectable by the naked eye due to abrasion. A small wisp of smoke, once more pronounced, becomes visible in a UV image of Men Smoking in an Interior. Surprisingly, this detail differs from the smoke exhaled by the same figure seen in a photograph of this painting included in the 1929 auction catalogue below.

Technical analysis with infrared reflectography (IRR) shows that the figures in this composition were outlined by the artist with a freehand underdrawing before they were worked up with additional paint layers. In IRR, carbon-rich areas done in charcoal or carbon black are differentiated and visualized because they absorb infrared rays that pass easily through other materials. This method is therefore particularly useful to reveal preliminary drawings often used by artists to sketch out compositions on the painting’s ground layer. These underdrawings were subsequently covered by other paint layers used to work out the work’s three-dimensional qualities in light, shadow, and color, and to provide texture. IRR did not show any significant deviations from this preliminary drawing in the final composition. Such changes are often regarded as an argument for originality, since an artist might make adjustments to his painting as the creative process unfolds. But when an artist works after an established composition, as we suspect is the case here, such changes are usually not needed.

Update 06/13/2020: A recent trip to the Netherlands Institute for Art History (RKD) in The Hague, which opened up to visitors again on June 2, allowed follow-up research in their collection of annotated auction catalogues. Several copies of the 1929 sale of the collection of Maximilian Kellner (1869–1940) in Berlin revealed that the Picker’s painting was highly valued at the time. While no buyer name was recorded, the work fetched the high price of 18,500 Reichsmark, or close to 140,000 USD in today’s currency.

While we often think of an artwork as the result of an individual creative process, sixteenth and seventeenth-century paintings were usually produced in workshops where many hands were at work. In addition to a master painter, assistants in various stages of their training helped to prepare paints, execute works based on the master’s designs, and make precise copies of completed works. Styles and compositions that were particularly popular could also be copied by other artists. Sometimes these copies were done in a much later period, and after prints rather than the original painting.

Multiple versions of Men Smoking in an Interior are known today, but this tavern scene probably did originate in the workshop of Adriaen Brouwer.

Evidently done by different hands, most versions likely follow a lost original by Brouwer. Experts think that our painting was created by a relatively skilled artist, and at one point could have included final touch ups by Brouwer himself.

An examination of the painting under UV light has revealed significant repairs to the abraded background done during at least two restoration campaigns. Materials that appear to have the same color in regular light, can fluoresce very differently under ultraviolet light (UV). As such, this process can reveal the extent of previous restorations or traces of composition elements that are no longer detectable by the naked eye due to abrasion.

A small wisp of smoke, once more pronounced, becomes visible in a UV image of Men Smoking in an Interior. Surprisingly, this detail differs from the smoke exhaled by the same figure seen in a photograph of this painting included in the 1929 auction catalogue below.

Technical analysis with infrared reflectography (IRR) shows that the figures in this composition were outlined by the artist with a freehand underdrawing before they were worked up with additional paint layers.

In IRR, carbon-rich areas done in charcoal or carbon black are differentiated and visualized because they absorb infrared rays that pass easily through other materials. This method is therefore particularly useful to reveal preliminary drawings often used by artists to sketch out compositions on the painting’s ground layer. These underdrawings were subsequently covered by other paint layers used to work out the work’s three-dimensional qualities in light, shadow, and color, and to provide texture. IRR did not show any significant deviations from this preliminary drawing in the final composition. Such changes are often regarded as an argument for originality, since an artist might make adjustments to his painting as the creative process unfolds. But when an artist works after an established composition, as we suspect is the case here, such changes are usually not needed.

Update 06/13/2020: A recent trip to the Netherlands Institute for Art History (RKD) in The Hague, which opened up to visitors again on June 2, allowed follow-up research in their collection of annotated auction catalogues. Several copies of the 1929 sale of the collection of Maximilian Kellner (1869–1940) in Berlin revealed that the Picker’s painting was highly valued at the time. While no buyer name was recorded, the work fetched the high price of 18,500 Reichsmark, or close to 140,000 USD in today’s currency.