A painting’s frame serves many different functions. It protects the work and secures it in place, and allows us to hang it on the wall for display. A frame also brings the painted composition in focus by providing an aesthetically pleasing border that complements the work in tone and style, and can help to integrate an artwork into an interior setting. But frames are also historical objects in their own right. Created by specialized artists and craftsmen, they can accumulate important information about the works they hold over time.

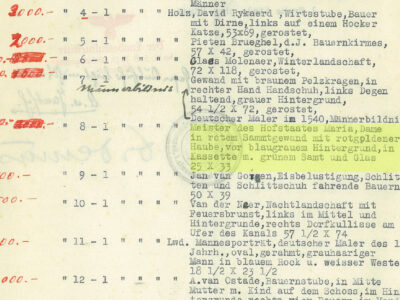

An inscription on the reverse of the gilded and gesso-carved softwood frame of Portrait of a Boy, Age 12, for instance, identifies the sitter as the English poet John Milton (1608–1674). Research into the veracity of this anonymous assertion is still inconclusive. But knowing that the portrait was thought to represent the famous poet in the past helps us to better understand past appreciation of the work and to find references to it in historical records, including auction catalogues.

![An annotated page from an auction catalogue that records a sale held in London in 1898, lists lot no. 15 as a portrait of John Milton at age 12, which sold for 13 pounds and 13 shillings to an “E. Kelly.” Catalogue of pictures by old masters from numerous private collections […] London, Christie, Manson & Woods, 23 July 1898, p. 4. Page from an auction catalogue with handwritten annotations in black ink along the margins indicating prices and buyers names, highlighted section reading "no. 15, Janssen, Portrait of Milton, Aetat 12"](https://worksinprogressexhibition.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/1_Christies-1898-07-23-lot-15-340x300.jpg)

A tavern scene by Adriaen Brouwer’s workshop came to the Picker in a frame that was originally made for a smaller painting. Cuts through the diagonal reinforcements in the corners show that the frame opening was enlarged to accommodate the larger panel. Unfortunately, the frame covered a disproportionate part of the painted surface as a result. For this reason, curators decided to give it a new frame that better allows viewers to appreciate the full composition.

Portrait of a Woman was held in a display case with a glass enclosure. We learn from a 1938 inventory of paintings owned by collector Max Oberlander that the work was already kept in this display case at that time. The portrait left Austria, in this case, two months after the country’s annexation by Nazi Germany. Despite a tumultuous life that included moves across continents, this container has thus served well to protect the work from damage over the past century.

A painting’s frame serves many different functions. It protects the work and secures it in place, and allows us to hang it on the wall for display. A frame also brings the painted composition in focus by providing an aesthetically pleasing border that complements the work in tone and style, and can help to integrate an artwork into an interior setting. But frames are also historical objects in their own right. Created by specialized artists and craftsmen, they can accumulate important information about the works they hold over time.

An inscription on the reverse of the gilded and gesso-carved softwood frame of Portrait of a Boy, Age 12, for instance, identifies the sitter as the English poet John Milton (1608–1674). Research into the veracity of this anonymous assertion is still inconclusive. But knowing that the portrait was thought to represent the famous poet in the past helps us to better understand past appreciation of the work and to find references to it in historical records, including auction catalogues.

![An annotated page from an auction catalogue that records a sale held in London in 1898, lists lot no. 15 as a portrait of John Milton at age 12, which sold for 13 pounds and 13 shillings to an “E. Kelly.” Catalogue of pictures by old masters from numerous private collections […] London, Christie, Manson & Woods, 23 July 1898, p. 4. Page from an auction catalogue with handwritten annotations in black ink along the margins indicating prices and buyers names, highlighted section reading "no. 15, Janssen, Portrait of Milton, Aetat 12"](https://worksinprogressexhibition.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/1_Christies-1898-07-23-lot-15-340x300.jpg)

A tavern scene by Adriaen Brouwer’s workshop came to the Picker in a frame that was originally made for a smaller painting. Cuts through the diagonal reinforcements in the corners show that the frame opening was enlarged to accommodate the larger panel.

Unfortunately, the frame covered a disproportionate part of the painted surface as a result. For this reason, curators decided to give it a new frame that better allows viewers to appreciate the full composition.

Portrait of a Woman was held in a display case with a glass enclosure.

We learn from a 1938 inventory of paintings owned by collector Max Oberlander that the work was already kept in this display case at that time.

The portrait left Austria, in this case, two months after the country’s annexation by Nazi Germany. Despite a tumultuous life that included moves across continents, this container has thus served well to protect the work from damage over the past century.